Speaking Story to the National Year of Reading

- Alastair K Daniel

- 10 hours ago

- 21 min read

This article is organised in the following sections:

In July 2025, Bridget Philipson, the Secretary of State for Education for England, announced that 2026 would be designated as ‘National Year of Reading’. The dedicated website says that:

‘...fewer of us are making time to read. With so many forms of entertainment at our fingertips, reaching for a book can feel like a chore. Something we should do, but don’t really want to do. But we believe it's just a matter of shifting the focus. So for the National Year of Reading in 2026, we're bringing reading to where culture is.’ [1]

Storytelling and reading are distinct practices (as will be explored in detail below), but it is my conviction that there is a relationship between them that can, if exploited, deepen learners engagement with print at the same time as providing them with rich experiences with spoken language. In the sections that follow, I will address the interconnectedness of spoken word and printed text, the nature of storytelling, the relationship between storytelling and reading, and (finally) make some practical suggestions on how this interrelationship can be celebrated and exploited to pedagogic ends.

From Spoken Word to Printed Word

Before looking at storytelling as a specific practice (and its relationship to reading), it is important to establish the interconnectedness of the spoken word and the printed word.

Spoken language (for most people) precedes being able to read and write, and emerges from the natural interactions between infant and parent, developing through conversations with others, and life-long opportunities to explore and play with talk. Spoken language is the foundation upon which written word is constructed, and the history of writing is grounded in people finding ways of preserving that which is spoken, and which would otherwise be lost in the instant of its utterance.

The dominant model for the teaching of reading in England is the Simple View of Reading. Gough and Tunmer developed the Simple View in 1986 as a way of explaining reading disabilities such as dyslexia [2]. According to the model [3], reading can be viewed as bringing together two complementary processes: word recognition and language comprehension.

Word recognition refers to the ability to recognise letter combinations as specific words, and associate the sounds associated with that combination of letters in order to pronounce that word. When we are unable to recognise a word, we need to employ strategies to work out which sounds of English relate to the letters before us. This is referred to as decoding and (in England at least) is taught by government edict through Systematic Synthetic Phonics (SSP). Using SSP, we see the letters D O G and recognise that they make the sounds /d/ /o/ and /g/, and that when we run those sounds together, we get the word ‘dog’. In other words, written letters are defined by the sounds with which they are associated: the written letter (or letter combination such as ‘ar’ or ‘ch’) being the transcription of the spoken sound.

When we read, we move from written word to spoken word; we see the written word and pronounce either aloud or in our heads) the spoken word [4].. Word recognition and decoding, then, (which are essential aspects of reading according to SSP), cannot be disassociated from spoken language.

The second aspect of the Simple View of Reading is language comprehension. When I teach SSP (to student teachers), there is usually some confusion between language comprehension and reading comprehension (indeed, this is not limited to student teachers, and I have known leading Ofsted inspectors to become confused over the same thing…). It is language comprehension that enables us to communicate with those around us through speaking and listening. It is language comprehension that means that if someone says the word ‘dog’, you are able to associate the sound of the word with a loyal canine with a cold wet nose, rather than (say) a venomous legless reptile.

Reading is, then, defined by SSP, as the application of language comprehension to print: words that have been recognised, either through prior knowledge or by decoding the letters into the sounds that they represent, are understood through their relationship to spoken language. Without being able to understand the meaning of the words that you can recognise (or decode) the words in a text, you are effectively doing nothing but ‘barking at print’ (as this has been referred to [5]). However, bringing language comprehension to printed text obviously goes beyond the word level, and we depend on being able to derive meaning from grammar (the way that words are combined), punctuation (which generally marks grammatical units), and conventions associated with genre, etc. This understanding is established through relating the printed word to spoken language and developing language comprehension.

Developing language comprehension is not, however, something that simply precedes the act of reading comprehension, but rather an aspect of learning which needs to be woven through approaches to literacy at all levels so that there is a continuous interplay between spoken and written word, between language comprehension and reading comprehension. Thus, oracy learning (which is the shorthand term for learning to talk, learning about talk and learning through talk[6]) is fundamentally intertwined with literacy learning.

This article is about the specific use of storytelling in the teaching and learning of reading. However, we need to recognise that storytelling is only one thread of oracy. As already established, the Simple View of Reading brings together decoding/word recognition and language comprehension as components of reading comprehension. However, reading comprehension includes aspects such as recognising the impact of text on feelings, the expansion of knowledge, the use of cultural cues, understanding the writer’s choice of language, etc.. Each of these aspects of reading comprehension is most effectively developed through talk-based teaching and learning strategies, which include: discussion, dialogue, debate, explanation, questioning, presentation and drama. The decision to use storytelling as a strategy to support reading therefore needs to be informed by awareness of how the particulars of spoken language as storytelling relate to the intended learning outcomes, as well as how storytelling is best deployed as a classroom strategy.

Supporting Reading for Pleasure through Playful Storytelling

According to the Year of Reading website:

The ambition is that the National Year of Reading 2026 will make lasting change to the reading habits of the nation to reverse the decline in reading for pleasure and unlock one of the most powerful tools for equity and opportunity: a love of reading that lasts a lifetime. [6]

The aim for the year is, then, focused on reading for pleasure. There are various descriptions of what reading for pleasure looks like, but one of the common threads is the notion of choice – that the learner has a choice over what they read, how much they read and when they choose to read (and to an extent, where they read). There is also an additional thread that running through the literature about the absence of accountability of the reader to someone in authority. This means that reading choices do not have to be justified, that the reader is not tested, nor are they expected to demonstrate knowledge or understanding of their reading.

It could be argued that starting from the definition(s) of reading for pleasure above, storytelling has little relevance to this aspect of literacy. It is, of course, possible that connections that I make below (and the example activity provided) could come about through learners choosing of their own volition to tell stories to each other. But this article is concerned with how we, as educators (whether teachers who tell stories, or storytellers who teach) support developing readers through employing specific strategies. By contrast, if any of what is suggested below forms a compulsory activity, rather than something the reader has chosen to do for themselves, then there is a conflict with a reader-centred understanding of reading for reading for pleasure.

All is not lost, however, and I suggest that placing an impermeable barrier between guided reading practice (or instruction) and reading for pleasure is unhelpful. While we need to understand what reading for pleasure looks like, the learner (of any developmental stage) needs to be able to derive meaning from the text that they have chosen. At every level, from the toddler ‘reading’ a picturebook out loud in babylese, to the university student making sense of complex research reports, the learner needs support. For the toddler support may come from having a parent or carer who reads aloud to them and demonstrates both the mechanics of reading a book (directionality, turning pages, etc.) and the meaning of the text through reading with expression; the university student may need a tutor who can model how to take a critical stance towards research findings through the way that they use academic texts in discussions.

To foster a life-long love of reading, then, educators have to do more than simply guide learners in the practice of reading (or give direct instruction). A positive attitude to reading needs to be fostered and, bearing in mind the interconnectedness of the four strands of reading, writing, speaking and listening, this itself needs to be embedded within ‘a language-rich environment – the “caught” as well as the “taught”’ [7]

When storytelling is integrated into classroom practice, teachers and learners demonstrate that they can ‘manipulate [their] words to creative ends’ [8]. I have observed a reception child decide to write a poem in response to a student-teacher storytelling extracts from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and another write an entire hybrid picture book (which combined fairy stories in a visual text which included lift-the-flap components) following a workshop developing a critical understanding of Little Red Riding Hood [9]. It’s also not uncommon for learners to go in search of books of folk stories when the teacher has shared tales with them, or to explore the life story of an historical figure whose biography a teacher has told.

My suggestion then is that, although reading for pleasure will not be evidenced during the storytelling activities discussed below, the very nature of storytelling means that it can foster engagement with texts and at the same time provide a sense of ownership for learners as they engage with them. While storytelling approaches can support the demands of the curriculum in relation to reading (at all ages and stages), it additionally can help learners to develop aesthetic responses to what they read, and in particular, what they choose to read. Keiran Egan has written:

The justification for reading at the elementary school is, simply, ecstasy - the intoxication that can be achieved by stimulation and use of the imagination. If we cannot get students to experience this, then all the sub-skill mastery in the world will be a sterile achievement. Egan, K. (1986) Teaching as Storytelling. Chicago University Press. P88

While, Egan is specifically addressing the needs of learners in the elementary (in UK terms, primary) school, I want to extend this idea to all reading: that even consulting information texts can be pleasurable when it is used to satisfy authentic curiosity. But I want to go further: separate from all the pragmatic justifications for using language in the classroom is ‘the intoxication that can be achieved by stimulation and use of the imagination’ that playful language can bring. We can say that storytelling, then, forms a natural part of the language-rich environment, where learners experience ‘the intoxication that can be achieved by stimulation and use of the imagination’ through language. Finding intoxication in language is surely a building block to reading for pleasure.

In the next section, we will look at what marks storytelling as a particular form of spoken language, how it relates to reading, and how specific aspects of storytelling can support reading.

Storytelling, a Definition

The definition of storytelling with which I have been working since 2021 is:

…an oral recounting of a narrative (or part of a narrative) that is reliant on the linguistic resources of the speaker (and is performed in the absence of a written text). [10]

It will be helpful to break down this definition into its key elements:

It is oral - storytelling is not story writing, it is spoken language;

It’s an oral recounting - it’s not acting. When we recount something, we stand outside the experience about which we are talking. In storytelling, our default position is outside the story world; in acting the default position is that we act as if we were inside the story world;

It is reliant on the linguistic resources of the speaker – it is not reciting an author’s text. Of course, we constantly draw on the language that surrounds us and draw words and phrases from other people’s speech, whether picked up in a conversation, heard in a TV show, or read in a book, but such language has become part of our own linguistic resource;

It is performed in the absence of a written text – it is not reading aloud;

It sometimes involves only telling part of a story rather than a complete narrative (beginning-middle-end) – this is probably the most common way that we use storytelling conversationally.

The word ‘storytelling’ is, of course, commonly used to refer to other practices: writing, choreography, dancing, acting, directing, painting, etc. While the use of ‘storytelling’ to label these other practices is legitimate, it is metaphorical. Carlos Acosta dances a story rather than tells it. Adjoa Andoh acts a story rather than tells it. Stephen Spielberg directs a story rather than tells it. And so on.

Storytelling, in the way that I have formulated it, is a specific oral practice: a crafted and (often) artistic spoken event. However, we need to remind ourselves that such artistic tellings derive from that everyday conversation through which we make ourselves known to other people through the stories we tell, and understand other people through the stories that they tell.

Storytelling: Performance and Process

In the recent past in England, storytelling in schools has generally been focussed on performance outcomes: either learners performing stories to each other or invited audiences (sometimes framed as competitions), or whole classes learning a story by heart (which by my definition is of course recitation, not storytelling).

While performance-oriented storytelling can be of benefit to the language skills and confidence of learners, it has limited practical application in the classroom, not least because of the time commitment required. Rather than storytelling as performance (or product), the discussion below focuses on storytelling as process. In process-oriented storytelling, we focus on the engagement of the learner in the moment of storytelling, rather than a rehearsed performance outcome.

Storytelling and Reading: Making Connections

By engaging in oral storytelling, with and for learners, we are able to exploit the interconnectedness of oracy and reading.

In Figure 2 above, I have identified a range of specific connections between reading and storytelling:

embodying language: connecting meaning, expression and fluency

exploring the nature of narrative, narrative language and specific stories

consolidating knowledge of narrative, narrative language and specific stories

critically evaluating narratives

developing ownership of narrative forms, narrative language and specific stories

creating alternative versions of narratives

While I have connected storytelling and reading with these aspects, each of them could (of course) be explored through discussion and dialogue around written texts rather than storytelling. However, talking about story is not the same as telling story. Talking about a story (educator with learners, and learners with each other) is a vital part of the teaching and learning process. However, talking about a narrative makes the narrative the object of spoken enquiry: it is something to be examined. When we tell a story, on the other hand, the story makes the characters and events the subject of expressive talk, creating a direct link between the teller, the story and the audience. In other words, it evokes an aesthetic response to the narrative.

Of course, reading a text aloud can be expressive and an aesthetic response. However, as explored above in the discussion of the Simple View of Reading, reading involves word recognition skills being applied to written texts. Words and sentence structures which are not often encountered, or which are unfamiliar, bring to the fore the mechanical demands of the process of decoding both the alphabetic code and the grammatical structures of English, to the detriment of fluency and expression. Storytelling does not make those mechanical demands.

When we read a book, we read the words and ideas of the author. They have shaped those ideas through language (and perhaps illustration) to communicate the story. That author is both distant and distinct. However, the author is not present with us in the room, and published authors have a privileged place that places them outside most classroom and family cultures. By contrast, when we tell stories orally (even if we are telling a story that is not our own), the person who is shaping the language is present with the listeners, and (if that person is a peer or teacher rather than a visiting storyteller) they are a member of the community - it is one of us who is shaping and ‘manipulating words to creative ends’ (Rosen 1991 [11]).

When we tell stories and manipulate words to create ends, we embody the language that we use. The non-verbal experience of telling a story involves breath, muscle tension, and gaze (and the other aspects in Figure 3 below). If we learn a story as a script, and rehearse and practice it, we will work out the right moments to breathe, at which points to raise or release tension and where to look while we are performing. As an exercise in making explicit connections between language and its embodiment, this way of learning can be useful, but in everyday life we naturally, if subconsciously, make these choices as we talk. If we are struggling to remember a point that we wanted to include while talking, we tend to look up or into the distance, defocusing from the immediate surroundings; when we have remembered what we wanted to include, but then want to manipulate our memory or work something out as we talk (perhaps to find the right wording), we will tend to look down. As we talk, then, we include our physical bodies in the communication.

However, while someone listening to us may well read our gestures, changes in muscle tension and shifts in gaze, helping them understand our meaning, this physicality is as much a part of our thinking as it represents our thinking [12]. When we choose to tell rather than read, we are freed from having to hold the text and engage in the mechanics of word recognition/decoding. We have the freedom to use our physicality to explore (and in turn express the story), and I suggest that this experience can then be applied to expressive reading: the reader recalling those changes in voice, tension, gaze and gesture as they told a story, which can then be used (even if they are internalised) in expressive reading.

Telling a story involves the sustained and coherent use of embodied language to communicate narrative. When we read a story, we give voice (either out loud or in our heads) to the author’s words and, as we do this, what are referred to as mirror neurons fire in our brains so that we share some of the experience of events that the narrative is portraying creating which might be referred to as a virtual embodiment [13] To be sure, these messages being sent in response to connections we make between the narrative and our own real life experiences. But we also rely on those vicarious experiences that we have absorbed from other texts, images, film, music etc. to create the connections,

I suggest that we can exploit these connections through both learners storytelling for themselves and educators storytelling with them creating that ‘language-rich environment’ together. An implication of this is, of course, that educators need to be able to model storytelling with learners. This does not mean performing a word-perfect performance in which every move is choreographed, but a preparedness to have a go, talk about how the story has been told, and make explicit the connections between storytelling reading (using, for example, those listed above).

What follows is an activity that I have used with leaners of a range if ages, and which provides opportunities, not only for fluent and expressive storytelling, but also for the playful exploration of moments of action, thought and dialogue can be differentiated.

Embodying language: connecting meaning, expression and fluency

The scope of this article means that I will only consider the first of the aspects identified in Figure 2: Embodying language: connecting meaning, expression and fluency. To do this, I will explore the connections between the expressive aspects of storytelling and those of story reading (both reading aloud and reading ‘in the head’), before providing an outline of storytelling activities to support fluency.

Timothy Rasinski, for the Education Endowment Foundation [14], defines fluency in terms of:

Accuracy

Automaticity

Prosody

Accuracy means that the reader is able to recognise familiar written language and decode unfamiliar ones (using their knowledge of phonics, common spelling patterns (such as prefixes and suffixes)), and able to do so without error. Developing this kind of accuracy means that they can read text without conscious effort when reading familiar language and are able to quickly decode the unfamiliar. Automaticity means that the reader can divert their metal resources away from the alphabetic code towards the meaning of the text, which is where prosody becomes relevant:

‘[The] component of fluency that links word recognition to comprehension is prosody (or expressive oral – and silent – reading). Think of anyone you would consider a fluent reader: not only do they decode words automatically, but they also read the words in texts with expression and phrasing that reflects and amplifies the meaning of the text. To read with appropriate expression and phrasing requires the reader to access the meaning of the text.’

Rasinski (2022) [15]

In other words, fluent reading and spoken language (even when it is internal, during silent reading) are connected. Quigley takes this point further linking prosody to ‘natural’ spoken language:

As they free up mental bandwidth by making such word reading automatic, [learners] have more space to consider the meaning of the language and go on to put the appropriate expression in their voice, etc. Their reading begins to sound ‘natural’, akin to how they may speak, with their pacing sounding like typical talk’. Quigley, A. (2020) Closing the Reading Gap. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis: 52

There is a problem, however, with this connection. As Quigley acknowledges, learners with limited skills in oracy will struggle to comprehend text and read with fluency. In addition, it was noted by many of the contributors to the report of the Oracy All Party Parliamentary Group, that the Covid 19 crisis had a detrimental effect on the spoken language of many children [16]. At the time of writing, the Covid 19 crisis is almost six years behind us; however, the impact of the lengthy lockdowns and resulting isolation for many learners is almost certainly still having an impact on the spoken language, and specifically oral fluency, of learners at all levels of education [17].

Bearing in mind, then, the interconnectedness reading and spoken language, I feel confident in making a connection (which is supported by research) between learners developing oral fluency through storytelling and future and/or parallel development of fluency in reading. [18]

Storytelling with Wordless Picturebooks

Wordless, or near wordless, picturebooks can provide a rich resource for supporting storytelling. The wordless book provides a storyboard which can be brought to life by the storyteller(s) without limiting or dictating the use of language (and the accompanying non-verbal aspects of communication). It also provides a common narrative thread for paired or group telling.

There are a range of strategies that can be applied to storytelling with wordless books, but I am going to outline how I have given learners sticky-notes to annotate wordless picturebooks and help them expand their narratives beyond action to include dialogue and thought. The process is outlined below in six stages which can be summarised as:

Part 1: Sharing the book

Part 2: Paired/Group Storytelling I

Part 3: Reviewing the storytelling I

Part 4: Developing the story

Part 5: Paired/Group Storytelling II

Part 6: Reviewing the storytelling II

Part 1: Sharing the book

In pairs or groups, learners share the whole of the book, discussing the characters and the events. In this way everyone is familiar with the story. If the pairs/groups tell the story without sharing the book first, they are unlikely to have the understanding of contexts, characters and the progression of events that will them to create a coherent narrative;

Part 2: Paired/Group Storytelling I

Learners sit in pairs or in groups so that they can see each other and the text (see Figure 4).

The pairs/groups tell the story using an object as a ‘talking-stick’ (which is passed from learner to learner indicating whose turn it is to speak).

- using a small object as the talking stick (such as a pen or lollipop stick) rather than something bulky (such as a soft toy) means that the teller to be able to move and use gestures while they are telling; - if the groups are of five learners or more, include the rule that the talking stick must be passed across the group rather than to the person next round the circle (this removes predictability and means that leaners have to listen carefully throughout the activity);- if the learners have sufficient confidence in spoken language, once they are comfortable in the routine of the paired/group storytelling, introduce the rule that the talking-stick can only be passed mid-sentence. This provides an additional element of unpredictability that helps maintain both the focus and the energy of the telling.

Part 3: Reviewing the storytelling I

Once they have finished their telling, the pairs/groups of learners review their storytelling: what went well and what would improve a future telling. As they discuss the storytelling, encourage them to not only say what they thought went well, or what could be improved, but why (e.g. What impact did changing the tone of voice have? How could listening to each other more closely change the paired/group telling?)

It may help the pairs/groups help to suggest that they consider:

How they have used their voices

How they have used gesture and movement

What essential elements of the story they have included

How they have used language

Whether they have listened to each other so that they could build on what has been already said

Part 4: Developing the story

Using sticky notes, learners add characters’ speech and/or thoughts to the pictures

Part 5: Paired/Group Storytelling II

The story is retold (again using the talking stick strategy) but, as learners tell the story, they try to include the thoughts/speech of the characters in the text.

Part 6: Reviewing the storytelling II The pairs/groups of learners review their storytelling once more: what went well and what would improve a future telling (explaining their answers as before). This time, however, they need to consider the inclusion of thoughts and/or speech these were made clear by the way in which they were included (e.g. through changes in voice, the inclusion of gesture, how they have related to the events and the actions of the characters).

Wordless picturebooks suitable for storytelling:

There is a wealth of wordless picturebooks available; here are a few that I have used with learners of a range of ages:

| Lita Judge (2011) Red Sledge. Atheneum Books for Young Readers | |

| Kevin O’Malley (1993) The Box. Stewart, Tabori & Chang . This book has been made available as a free downloadable PDF at http://www.booksbyomalley.com/free-pdf-books/the-box-by-kevin-o-malley.pdf (accessed 4/2/26) | |

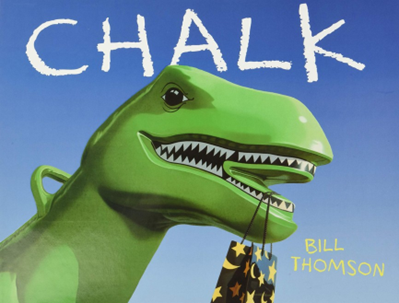

| Thomson, B. (2010) Chalk. Two Lions: Las Vegas NV | |

| Gregory Rogers (2004) The Boy, the Bear, the Baron, the Bard. A&U Children | |

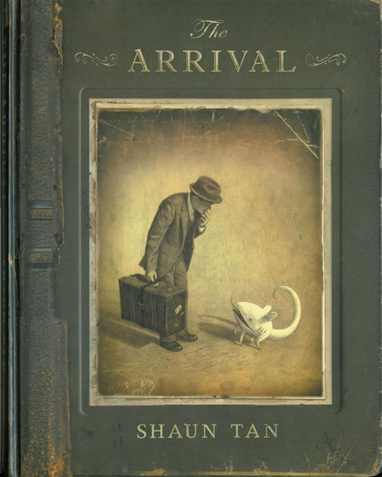

| Shaun Tan (2014) The Arrival. Hodder Children's Books |

NOTES

[1] Oracy Education Commission. (2024). We need to talk: The Commission on the Future of Oracy Education in England: 14. Available at: https://oracyeducationcommission.co.uk/oec-report/ (accessed 5/2/26)

[2] Gough, P.B. & Tunmer, W. E. (1986) Decoding, reading and reading disability. Remedial and

Special Education, 7, 6-10.

[3] Gough and Tunmer’s use the word ‘model’ here is important: reading is far from a simple process, and their model is not an overarching theory of reading. When I am teaching the Siple View of Reading to student teachers, I show them my model of a 1960s trolley bus that used to run in Maidstone in Kent. We discuss what the model tells them about a 1960s trolley bus. Clearly, it tells us that a trolley bus is similar to a double-decker bus, it has space for passengers, the driver sits at the front and the livery for Maidstone Corporation trolley buses in the 1960s was cream and brown.

However, it does not tell us the dimensions or weight of the trolley bus, nor anything about the propulsion system, nor does it help us to understand what the experience of travelling on one of these vehicles was like. In other words, a model is designed to show particular aspects of a phenomenon and make those clear, while not communicating anything substantive to our understanding of other aspects.

Similarly, the Simple View of Reading helps us to see how reading can be viewed as being composed of the complimentary skills of word recognition and language comprehension. However, the Simple View doesn’t explore the relationship of comprehension to culture, the critical aspects of literacy concerned with power and representation, or how readers respond emotionally to what they are reading (among many other aspects of the reading process).

[4] As readers become competent, they start to be able to read in their heads faster than reading aloud, not necessarily mentally articulating the word, but simply recognising it and deriving meaning from it without the need to engage in the time-consuming process of making or hearing the sound of the word.

[5] Hodgson, J. (2018) Reading in the Reception Classroom. FORUM Volume 60, Number 3, 2018, pp337-344: 342

[6] Available at https://www.goallin.org.uk/frequently-asked-questions (accessed 2/12/25)

[7] Gross, J. (2018) Vocabulary – caught or taught? In Why Closing the Word Gap Matters: Oxford Language Report: 12. Available at: https://www.oup.com.cn/test/word-gap.pdf (accessed 20/1/26).

[8] This phrasing is inspired by a question posed by Mary Rosen in the introduction to Shapers and Polishers:

Many teachers of art paint pictures, woodwork teachers will turn bowls or make furniture, teachers of dance show how to move to music and whoever heard of a music teacher who could not play an instrument or sing a note? These people are not practitioners of their craft in the professional sense that they earn their living from these activities, but their real strength is in their capacity to do as well as teach. Few teachers of language, however, actually write - or even consciously talk - creatively, in the way that we expect our students to do. Thus we neither develop our own language as we could nor surprise ourselves by our own skills in manipulating words to creative ends.Rosen, B. (1991) Shapers and Polishers: Teachers as Storytellers. London: Mary Glasgow Publications: 6-7

[9] While these two examples highlight learners deciding to write, they reflect the children’s engagement with print more generally. The child writes a poem to be read. The lift-the-flap book demonstrates how the child has engaged with published playful texts and enjoyed the revelatory aspect of the lift-the-flap mechanism.

[10] Daniel, A. K. (2021) Storytelling – the social art of language. In Ogier, S. And Tutchell, S. (Eds.) 'Teaching the Arts in the Primary Curriculum’. London: Sage: 58

[11] Rosen, B. (1991) Shapers and Polishers: Teachers as Storytellers. London: Mary Glasgow Publications: 7

[12] There is a lot of research currently about the embodied nature of cognition (including emotional responses). According to Mark Johnson:

At the human level, cognition is action - we think in order to act, and we act as part of our thinking. Johnson, M. (2007) The Meaning of the Body: Aesthetics of human understanding. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, p120

[13] See, among others, Gottschall, J (2012) The Storytelling Animal: How stories make us human. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: 60-65

[14] Rasinski, T. (2022) Why focus on reading fluency?. Education Endowment Foundation, available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/news/why-focus-on-reading-fluency (accessed 19/1/26).

[15] Ibid.

[16] The Oracy All Party Parliamentary Group (2021) Speak for Change: Final report and recommendations from the Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group Inquiry. Available at: https://www.education-uk.org/documents/pdfs/2021-appg-oracy.pdf (accessed: 19/1/26)].

[17] Fluency as a universally applicable term in reading is also problematic in relation to learners with speech impediments and the 2024 We Need to Talk: The report of the Commission on the Future of Oracy Education in England: Commission on the Future of Oracy Education in England (2024) We need to talk. Available at: https://oracyeducationcommission.co.uk/oec-report/ (accessed 1`9/1/26)] makes a call for fluency to be reframed as ‘good communication’ (p44), avoiding an idealised form of spoken language. Speech impairments, of course, can present challenges to storytelling, and so bearing in mind that speech behaviours such as stammering or stuttering can be exacerbated by stressful situations, any teacher or storyteller intending to use storytelling as a strategy needs to be conscious of the need to create safe and non-threatening contexts within which learners can explore story through spoken language (such as paired tellings, or telling within a small group of familiar peers).

[18] Research findings that support this assertion including :

Panca, I., Georgescub, A., Zahariab, M. (2015) Why children should learn to tell stories in primary school? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 187: 591 – 595

Nicolopoulou, A. (2017) Promoting narrative skills in low-income preschoolers through storytelling and story acting. In Cremin, T., Flewitt, R.Mardell, B. and Swann, J. (eds) Storytelling in Early Childhood: Enriching Language, Literacy and Classroom Culture. Abingdon: Routledge: 49-66]

Comments